On Blind, Anonymity Leads to Camaraderie and Recruiting

On the internet, anonymity generally leads to trolling, hate speech, and maybe, if we’re lucky, a funny meme or two.

But things are different on Blind, the exclusive, anonymous communication app where the employees of tech giants congregate to trade stories and share news. There, anonymity leads to transparency, camaraderie, and even the occasional job offer.

A Workplace Tool Employees Can Actually Use

Founded in South Korea in 2014, Blind really began to gain attention in the U.S. earlier this year, when it became a reliable source for reporters looking to learn more about the much-publicized turmoil at Uber.

But Blind wasn’t exactly founded with leaks in mind. Rather, it began life and still primarily functions as an employee-centric community-building app.

“There are so many ‘tools,’ for the workplace, but they are all geared for the employer,” says Alex Shin, Blind’s head of U.S. operations. “There is more to work than employee surveys and productivity. We spend a third of our lives working, yet there is no place for professionals to just go and mingle with professionals.”

The team behind Blind launched the app as a tool that would fill this gap, something to help professionals navigate their workplaces and communicate honestly with one another. Blind is not a free-for-all; the app is only available at certain companies, mostly major tech firms like Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, and so on. Aside from private company channels, users can also chat across companies via the “Tech Lounge” channel or use the public “Topics” channel to reach an even wider audience.

In a way, the app is counter-hierarchical: Employees operate totally anonymously on the app, putting everyone from the newest hire to the CEO on equal conversational footing.

“We believe what is said is more important than who had said it,” Shin says. “Whether you are an intern or a V.P., you can have candid conversations and really understand how everyone is feeling.”

Indeed, this is largely the direction in which Blind has gone, operating as a channel for workers to discuss company culture, events, and new developments with their coworkers and with colleagues from other tech-industry giants. For example, many Google employees turned to Blind to discuss the events surrounding James Damore’s diversity manifesto, with the average user at Google logging 69 minutes of usage per day as the situation unfolded.

“We purposely left very little onboarding and never directly communicated with our users about what Blind was about,” Shin says. “Professionals can find their own need. They can also moderate themselves. We’re not about censorship, so the tone of Blind is very authentic. If a company is doing great, you’ll feel it immediately. If there are layoffs hitting your company, you’ll feel that, too.”

Blind’s usage numbers suggest tech workers have really taken to the app: The average user logs in four times and spends 41 minutes total on the app every day.

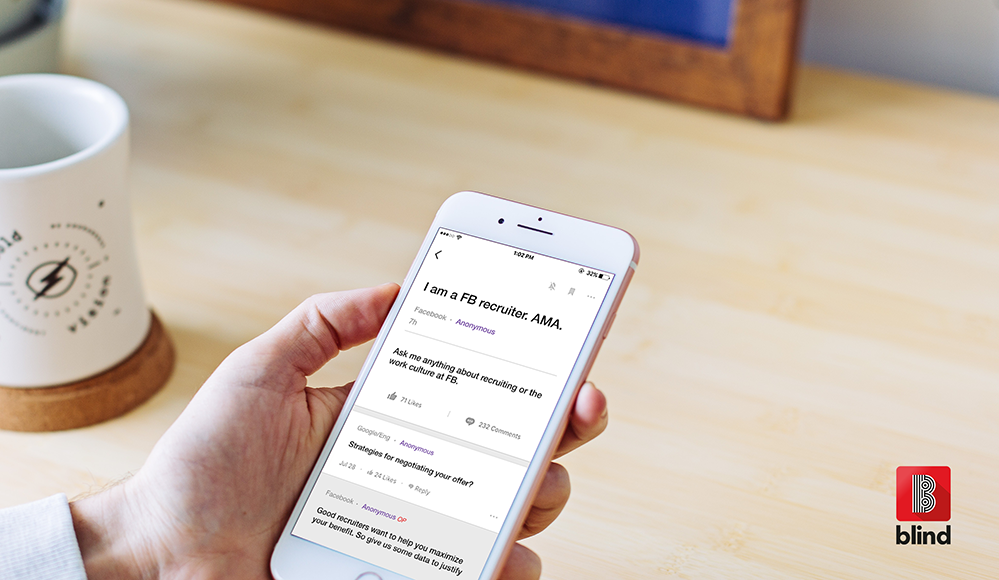

A shot of Blind in action

Anonymous Recruiting?

If there’s a new business app, someone will eventually use it for recruiting – which is exactly what happened to Blind.

While the app’s users in South Korea tend to search the platform for “advice, relationships, and venting,” according to Forbes, the search queries of U.S. users “indicat[e] a prominent interest in new [job] opportunities and generally exchanging information amongst each other.”

“When you collect a massive user base of people from top-tier tech companies, cross-pollination is just bound to happen,” Shin says. “People want to benchmark their careers, their savings, [and] their needs with other people who are similar to them.”

While an anonymous app might seem like an odd place to source new talent – after all, you don’t really know who anyone is – Shin says Blind users have come up with a variety of inventive ways to connect with one another regarding job opportunities. For example, it’s quite common for engineering managers and recruiters to host AMAs (“Ask Me Anything” sessions) where professionals can pose questions about life and work at certain companies and receive honest answers. Shin also notes that when Yahoo! underwent a round of layoffs earlier this summer, “users from Uber, Pinterest, Google, Facebook, and Lyft all chimed in to hire people” on threads about the layoffs.

“It’s a beautiful thing,” Shin says.

The Upsides of Anonymity

The interactions between users on Blind truly are impressive in their generosity and transparency – but they are also slightly baffling for those very same reasons. Anonymity doesn’t often lead to such positive communities.

Shin says Blind knew anonymity could be a risk from the start, and the team behind the app put in a lot of work to make sure Blind didn’t turn out like other anonymous-communication apps that devolved into hate speech and negativity.

“We worked hard on making sure that the voice of our community was authentic and informative,” Shin says.

That’s why every user has to verify with a work email address – although, after the verification, even Blind can’t match anonymous posts to email addresses. This verification step prevents the app from becoming a digital “Wild West” of sorts. Instead, only employees of certain companies can join, which goes a long way toward ensuring that conversations stay friendly, relevant, and productive.

Blind’s efforts to foster a genuine community seem to be paying off: Less than .05 percent of conversations on the app are flagged by users.

“At Blind, we’re all about identity and community,” Shin says. “When things are anonymous, you have to focus on voice. Users have no photos, no context, nothing that would help them decide what to say or how to behave. But if the content they first see is relevant, interesting, and sounds like someone you might know because they work on your floor or [at] the company next door, it creates identity, even though you are still completely anonymous.”

–

“Employees are the biggest asset to an employer, but there has never been a safe, honest, relevant place for employees to go to,” Shin says. “Managers are employees, too. So are HR people. So are V.P.s. Everyone has a boss, a coworker, a career goal.”

What Blind ultimately aims to do is challenge the notion that “you are bound to your manager or your company.” Instead, Blind fosters the notion that “employees are bound to each other by a common mission and vision,” Shin says.

By encouraging these bonds across companies and throughout the tech industry, Blind is also fostering a new approach to recruiting. Rather than an arms race, recruiting becomes an act of community-building. Tech professionals connect; they bond over common values; they share insiders news with one another. And every once in a while, they jump ship.