Hiring Pessimists

MILD AND EXTREME PESSIMISM/Image: Michael Moffa

“We all agree that pessimism is a mark of superior intellect.”—John Kenneth Galbraith, Harvard economist, author and presidential economic adviser

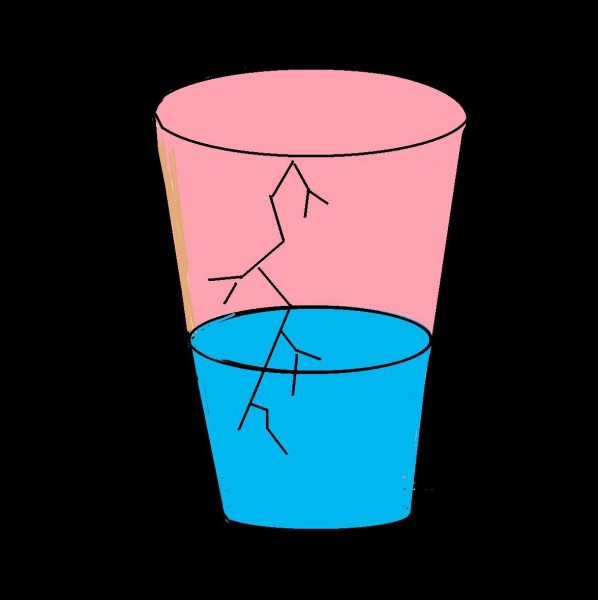

Imagine you are considering two comparable job candidates, one who seems, on the basis of his or her remarks and in general, to be quite the optimist, while the other, quite the pessimist. Other things being equal, which would you favor hiring, given that you must choose? Or would you prefer, instead of the “glass-half-full” optimist or the “glass-half-empty” pessimist, the “glass-not-cracked” wait-and-see-what’s-next type?

Workplace pessimism takes various forms and has multiple consequences and implications. On the one hand, and depending on what you understand pessimism to be, it can be an obviously serious professional and personal drawback. In the negative extreme, and understood as (a) the doctrine or belief that the existing world is the worst possible; (b) the doctrine or belief that the evil in life outweighs the good; (c) the tendency to expect misfortune or the worst outcome in any circumstances; or (d) the practice of looking on the dark side of things (Merriam Webster), it can easily lead to or be triggered by cynicism and fatalism—two attitudes virtually guaranteed to cripple work performance and poison the workplace atmosphere.

For example, and in connection with workplace relationships, a 2009 UK National Lottery study, “Optimism: a Report from the Social Issues Research Centre ”, reported that “over 50% of those surveyed preferred the company of optimists compared with a mere 3% who were more attracted to pessimists.” If that’s a general preference, it’s also virtually certain to be a workplace preference as well.

On the other hand, in choosing between between optimists, pessimists and what I call “what’s-next?-ists” (who represent an alternative to being an optimist or a pessimist), you might be influenced by a widely-publicized recent study that, as interpreted in the mass media, reportedly found that pessimists live longer and healthier lives than optimists—a finding with clear implications for workplace performance and tenure.

The Friedman Longevity, Health and “Pessimism” Study

That large-scale scientific study has been reported in the media as concluding that “pessimists” live longer healthier lives than optimists do. A rigorous 90-year University of California, Riverside study of 1,500 people tracked over their lifetimes, it was a continuation of the pioneering research of Louis Terman that began in 1921 (famous for inventing the Stanford-Binet IQ test and his studies that showed high IQs correlate with better, not worse, physical, socio-economic and mental health). The recent research, published as a book titled “The Longevity Project: Surprising Discoveries for Health and Long Life from the Landmark Eight-Decade Study” (Hudson Street Press, March 2011), was co-authored by Howard S. Friedman, distinguished professor of psychology at UCR, who led the 20-year study, and Leslie R. Martin, a UCR Ph.D., with the help of a cadre of about 100 graduate and undergraduate assistants.

Among the key findings of the study, the following are crucial to the question of the impact of pessimism on longevity and health, and, derivatively, to workplace health and performance:

- “We found that as a general life-orientation, too much of a sense that ‘everything will be just fine’ can be dangerous because it can lead one to be careless about things that are important to health and long life. Prudence and persistence, however, led to a lot of important benefits for many years.” (Friedman, Ibid.)

The implication here is that optimism breeds dangerous complacency, perhaps as a kind of superstition that one is invincible, that luck is on one’s side, or that the universe or the gods are watching over and protecting us as the 2007 New-Age movie “The Secret” suggests. Don’t worry about being unemployed, darting across a busy freeway or smoking heavily—“everything will be just fine.”

(Yet, other studies show that optimists are less likely to smoke—which, nonetheless, logically and statistically, is not the same thing as saying that smokers are less likely to be optimists. That’s the difference between saying that optimists won’t risk smoking and saying that risk-taking smokers are optimists. Although optimists tend not to smoke, smokers tend to be optimists—which supports the Friedman conclusion that pessimists live longer, if we are talking about smokers who might otherwise smoke more and die sooner.)

- “One of the findings that really astounds people, including us, is that the Longevity Project participants who were the most cheerful and had the best sense of humor as kids lived shorter lives, on average, than those who were less cheerful and joking. It was the most prudent and persistent individuals who stayed healthiest and lived the longest.” (Quoted in the Science Daily article “Keys to Long Life? Not What You Might Expect”, March 12, 2011.) (Italics mine.)

“Cheerful” = “Optimistic”? “Prudent and Persistent” = “Pessimistic”?

Notice here how “cheerful” seems to be strangely contrasted with “prudent and persistent”.

Apart from the logical oddity of opposing ”cheerful” and “prudent/persistent”, there is the peculiarity of identifying “cheerful” with “optimistic” and “prudent, and persistent” with “pessimistic”—conceptual mappings that the study and the media, respectively, seem to have endorsed.

Why can’t a cheerful person also be prudent and persistent, and why identify these with being optimistic and pessimistic, respectively? Surely pessimists are not, in virtue of their dark view of things, far likelier to be more persistent (conscientious), even though, for obvious reasons, more prudent and cautious.

Even the weighty and analytical The Atlanticmagazinetacitly equated pessimism and conscientiousness in its March 2011 article about the Friedman study : “For instance, optimistic people have a tendency to ignore details, meaning they don’t follow doctor’s orders correctly or lead themselves into unhealthy situations or addictions. It was the conscientious people—careful, sometimes even neurotic, but not catastrophizing—who lived longer, write Friedman and Martin, researchers at the University of California, Riverside.” [Italics mine.]

Pessimism and caution may correlate, but they are not equivalent and don’t translate into “conscientiousness”. So, it is one thing to argue that conscientiousness and prudence promote longevity; it is quite another to trumpet that pessimism does.

The key omission to note is that although the study included pessimism as one of the many investigated traits, habits and attitudes of the subjects, it is not explicitly mentioned in these media-highlighted conclusions. Neither is optimism, except indirectly and by inference, as “a sense that ‘everything will be just fine’”.

To the extent that “the tendency to take the most hopeful or cheerful view of matters or to expect the best outcome” (Merriam Webster) is difficult to distinguish from what Professor Friedman’s cited as “a sense that ‘everything will be just fine’”, it is tempting to equate the latter with optimism. Accordingly, given this definition and logic, the opposite of this must be pessimism. Hence, the widely disseminated media headline “Get Grumpy: Pessimists Live Longer Than Optimists”, despite no mention of pessimism in any of the extracted conclusions and quotes.

In the face of such contradictions, the intelligent response is to look for design and sampling flaws in one or more of the research protocols, to look for disparities between the sampled populations, e.g., to determine whether the age groups, genders, socio-economic variables, lifestyles, etc., were not the same from one study to another or not controlled for. Importantly, differences in definitions of the core concepts should be suspected.

These gender and age differences in sample populations may be highly relevant differences, in the same way that the following reported research finding notes a key gender-based difference in health and longevity:

Although you probably don’t screen applicants for optimism and pessimism, like the news media, you may informally or unconsciously gauge and infer these from a candidate’s “personality ”, e.g., the degree to which he or she is confident, extroverted, carefree, enthusiastic, cheerful or ebullient. Despite not being strictly synonymous with pessimism or optimism, these and other related traits are likely to significantly correlate with gloom vs. bloom mentalities—or at least be treated as such by some researchers and some media reporters. Nonetheless, as suggested herein, they are not equivalents.

Worse than this fuzziness, if not outright sloppiness in media reporting of the “benefits” of pessimism, is the existence of numerous contradictory studies that report the reverse: the claim that optimists live longer than pessimists. For example, a 2011 study by, Benjamin P. Chapman et al. titled “Personality and Longevity: Knowns, Unknowns, and Implications for Public Health and Personalized Medicine”, in which “optimism” and “pessimism” are defined as “a stable tendency to expect positive future outcomes” and “a stable tendency to expect negative future outcomes”, respectively, gives optimism the edge, but substantially hedged:

“…mixed evidence has emerged on the association of optimism with immune function, with one hypothesis being that optimists may experience more frustration when they do not experience immediate success and/or persist longer in stressful situations because they expect positive results.”

Gender and Age Differences

For example, several of the studies reporting better health and longevity for optimists sampled only women, with at least one limited to older women, whereas the Friedman study tracked both males and females,with an emphasis on their childhoodattitudes. This possibility of gender-specific differences in longevity due to differing degrees of optimism/pessimism, in addition to the aforementioned divergent or unconventional definitions of these, is well-illustrated by the following excerpt from a 2009 Reuters article titled “Optimists Live Longer and Healthier Lives: Study” :

“Researchers at University of Pittsburgh looked at rates of death and chronic health conditions among participants of the Women’s Health Initiative study, which has followed more than 100,000 women ages 50 and oversince 1994.

Women who were optimistic — those who expect good rather than bad things to happen — were 14 percent less likely to die from any cause than pessimists and 30 percent less likely to die from heart disease after eight years of follow up in the study.

Optimists also were also less likely to have high blood pressure, diabetes or smoke cigarettes.

The team, led Dr. Hilary Tindle, also looked at women who were highly mistrustful of other people — a group they called “cynically hostile” — and compared them with women who were more trusting….’Cynically hostile women were 16 percent more likely to die (during the study period) compared to women who were the least cynically hostile,’ Tindle said.

They were also 23 percent more likely to die from cancer.” (Italics mine.)

“Neuroticism predicted worse physical health and subjective well-being in old age and, for women, higher mortality risk, but for men, neuroticism predicted decreased mortality risk.” (“Personality and Health, Subjective Well-Being, and Longevity”, Journal of Personality 2010 Feb;78(1):179-216.)

Women Can Afford to be Optimistic?

Likewise, it may be that pessimism, interpreted in terms of prudence, is advantageous for men, but not for women, because prudence offsets in pessimistic males the reported statistical, if not innate, tendency of males to take more kinds of risks than women, e.g., in extreme sports, bar fights, combat, monster-truck rallies and smoking.

This is something that the weight of evidence suggests, e.g., evolutionary psychology studies reporting that males take risks to attract females (although some studies downplay the differences).If not so predisposed to taking life-and-health, endangering, financial and other risks (pregnancy, aside), women can afford to be optimistic, because, as a demographic group, they will not need the same level of prudence and vigilance as a corrective to any predilection to engage in extremely risky behavior (which is not to deny the existence of female skydiving, unsafe sex and entrepreneurial daredevilry).

The IRS and FDA Case for Hiring Pessimists

If pessimism is understood to be merely the general or situational reluctance—for whatever reason—to expect a positive outcome or development or the stronger additional inclination to expect something bad (not necessarily “the worst”), a pessimistic attitude can be a valuable professional and life asset. The reason is that this milder form of pessimism, as contrasted with toxic cynicism and paralyzing fatalism, can positively correlate with life and health enhancing prudence and persistence (“conscientiousness”).

If what might be called “rational evidential pessimism”, in contrast to neurotic or emotionally-motivated “emotional dogmatic pessimism”, is the form workplace and home-life pessimism takes, it can be a reflection of a very healthy mix of persistence, prudence, skepticism and caution—four of the highest professional virtues in conservative organizations, for example, the FDA (to the extent that corporate lobbyists have no influence on a given FDA ruling or policy) and the IRS (to the extent that it is inclined to very closely scrutinize your claimed deductions).

In practical and scientific terms, this kind of healthy pessimism correlates with useful vigilance—not oppressive, paralyzing anxiety, focused on preventing “type 1 errors” — the mistake of taking a risk and accepting a given hypothesis, a job applicant, a drug, a service, etc., that you shouldn’t, as opposed to a “type 2 error” of cautiously rejecting one you should have accepted.

Micro and Macro Pessimism

Hiring a pessimist or being one yourself can indeed be smart, again, depending on how “pessimist” is defined, while bearing in mind the obvious fact that many, if not most, people are pessimistic about some things and optimistic about others—especially about personal “micro-issues” the UK study calls “little” and the broader “macro-issues” of the economy, politics and society it dubs “big”. This difference is vividly illustrated by one of the study’s poll responses, in which family (72%) and personal health (65%) were seen as key influences on how optimistic people felt, whereas the global economy and global politics were important influences on levels of optimism for only 12% of poll participants.

Nonetheless, even though macro-issues seem to exert a small influence on the population as a whole, they can overshadow the “big” personal and family influences in any individual candidate’s or recruiter’s case—especially if the current state of affairs and health at home is much better or promising than the state of the existing affairs and health of the State.

Your Optimal, if not Optimistic, Hiring Strategy

Given current worrying levels of unemployment, the unnerving debt-ceiling crisis, the recent government credit downgrade, withering droughts, rampant home foreclosures and myriad other spooky problems, if you are looking to hire pessimists, these days they shouldn’t be hard to find.

But you should try to be optimistic and hope that it will be possible to recruit a prudent and persistent pessimist instead of a resigned cynical fatalist. If that kind of optimism about pessimism is not an option for you, there is one last resort.

You can try to find, hire and settle for an optimist.