Geologists Make Bad Recruiters

“Color: Minor color tonal variations exist but within the tolerance limit….Hardness: 6.5 to 7 on Moh’s Scale… Density: 2.3 to 2.4 Kg/cm3… Water Absorption: 1.0% – 1.2 %… Porosity: Low to very low… SiO2: 95%-97%”—Variation range of selected sandstone properties, www.mineralszone.com

Wouldn’t it be nice if candidates were as easy to read as rocks?—If only all of their “states” were enduring “traits”, so that you wouldn’t have to guess whether you are dealing with an attitude, a skill or a response that is actually atypical for her; or is merely transient, like a bad-hair day; or have to wonder whether what just happened between you was more of a reflection of your personality than of hers?

Ah…to have, in vetting a candidate, the confidence of a geologist in cracking the next rock that the fragmentation will follow a predictable pattern, for invariant reasons, always and with virtually no or only minor exceptions, e.g., a tendency to crack into exactly three large pieces, with attendant splinters and smaller fragments. It would also be reassuring to have the absolute certitude of a geologist who, just by looking at a rock, knows whether he’s observing its natural, essential grain or merely the accidental effects of weathering.

The Illusion of Text Democracy

You are writing a summary of a job candidate and note that she is “enthusiastic”, “poised”, “knowledgeable”, “responsible”, “professionally attired”, “argumentative”, “perceptive”, “serious” and “deferential”. The “democracy of text”—the visual impression and illusion that all written words are created equal and carry the same weight just because, as text, they have the same flat look and comparable length— may erroneously suggest to others or to yourself that the aforementioned candidate attributes are

1. equally evident (to casual observation)

2. equally substantiated (by the evidence available to you)

3. equally persistent (resistant to “extinction” in the candidate’s behavior)

4. equally intensely manifested (to a high degree)

5. equally frequently displayed (over a long interval of time and over a broad range of situations)

6. all triggered or inhibited by something in the candidate’s character

7. all character or personality traits, not merely transient states

8. all reflections of and on the candidate, not of the situation or of your traits or states

That these are possible errors of judgment and why they are can be elucidated by further comparing a recruiter with a geologist.

Rocks vs. Job Candidates

Recruiters and geologists, alike, sort, classify and evaluate their “samples” (rocks, candidates). Both utilize an extensive “attribute vocabulary” to characterize these as well as “tools” and tests for probing and examining them.

But there is one key difference that makes being a geologist easier than being a recruiter—a difference that makes most geologists professionally unprepared for the complexity of recruiting: Rocks, unlike candidates, are mostly a collection of physical and chemical properties inherent in their rock nature—properties that are stable, enduring, fixed, “essential” (rather than “accidental”), predictable, uniform from one rock to another of the same type and equally well-evidenced. Whatever role “nurture” and experience play in the shaping of rocks is usually obvious, e.g., weathering, fragmentation, erosion—not so with candidates.

Obvious though the differences between rocks and people should be, they are easily ignored or unrecognized, with the result that candidates are at risk of having accidental or transient states of mind and behavior in interviews perceived as essential and persistent traits, like those of rocks in the hands and under the gaze of geologists.

Yes, it’s much easier to be a geologist testing and identifying rocks. Rocks, unlike candidates, do not have mood swings; bad days; preferred or opportunistic strategies and tactics; states (e.g., being wet after a rainstorm) that are likely to mistaken for traits (e.g., a “predisposition” to being wet), shifting priorities; a capacity for sudden emotional, behavioral or volitional reversals; an ability to hide facts about themselves; or ambivalence.

Not only is one slab of sampled sandstone or limestone pretty much like another, but also each of the defining characteristics of any one slab is stable, enduring, resistant to change under normal circumstances, continuously displayed, independent of the observer and in possession of the foregoing attributes to the same degree as all the other defining characteristics—for example, brittleness, electrical conductivity, porosity and radioactivity.

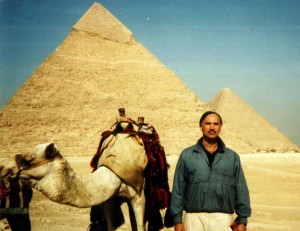

If you have any doubts about this, look at the accompanying photo.

The 2.3kg-2.3 kg/cm3density of sandstone doesn’t vary much within and between specimens and doesn’t depend on which geologist is assessing it. For any trait, property or attribute, a rock is far more likely to display it uniformly and consistently, and to do so to the same degree as another rock of the same type, irrespective of the day of the week (or the millennium) or the attitudes and behavior of the geologist. Again, not so for candidates—something that is sometimes forgotten.

True, one geologist may smack a rock harder than another and make it shatter rather than merely fracture, just as one recruiter may probe more aggressively than another. Despite this, the pressure required to fracture or shatter that rock is an enduring, stable, predictable characteristic of the sandstone that doesn’t depend on whether that force is in fact under- or over-applied.

However, resistance to shock or pressure is far more variable for any given candidate and among otherwise very similar candidates than it is for rocks.

Non-Rock Assessment

A recruiter’s job of vetting a candidate is much harder than a geologist’s job of examining a rock. Unlike the testing and assessment of sandstone, the assessment of a candidate requires that much more attention be paid to

– the degree to which a trait is manifested (how “argumentative”?)

– how frequentlythe trait is manifested (how frequently “argumentative” with you, with others?)

– how resistant to change the trait is (how “incorrigible” or “correctable”?)

– what seems to trigger or inhibit the trait/state (what caused or is likely to [have] cause[d] her being “argumentative”?)

– whether it is a trait, or a state (Is she an “argumentative” person, or merely having an “argumentative” moment?)

– how each of these varies from one individual of the same “type” to another (how does she compare with other candidates with respect to “argumentativeness”?)

These are not issues that often arise with homogenous sandstone samples and examination of them. Yet, there may be a temptation to ignore these differences between rocks and people, and to treat candidates as though they are as homogenous individually or even collectively as rocks can be. Based on the foregoing analyses, this mistake will manifest itself in the following ways:

1. FAILURE TO NOTE DIFFERENCES IN DEGREE OR INTENSITY OF A TRAIT OR STATE: A recruiter may fail to distinguish one candidate who is somewhat brittle or argumentative in an interview from one who is extremely so, by describing both as “argumentative”, without qualification. Or, the failure might be to assume that a particular candidate’s being extremely argumentative with you means “always” being equally argumentative, period.

2. IGNORANCE OF FREQUENCY OF TRAIT DISPLAY: One of the most alluring temptations is to over-generalize about how frequently a trait will be displayed by a candidate. Just because she is very well dressed on the day of the interview is an insufficient basis on which to conclude it’s her habitual style.

She may simply be playing by the interview rules and dress for that day only. On the other hand, “sloppy applicant, sloppy employee” is, barring little or no advance notice given to the applicant, a more reliable inference. Hence, the frequency with which a trait is likely to be displayed depends on the trait and the surrounding circumstances.

Therefore, recruiters should be very cautious in making assumptions about how often what they are seeing will be exhibited by the candidate after placement.

3. FAILURE TO GAUGE “HABIT STRENGTH”: Traits manifest themselves as habits. It is one thing to identify the trait and confirm that a candidate possesses it. However, it is quite another to estimate the strength of that habit, understood in terms of its resistance to “extinction”, i.e., in terms of how hard it is to shape or eliminate that habit. Accordingly, it will be virtually impossible to estimate in a job interview or on the phone how strong any candidate’s habit is.

Consider an interview with a smoker. From the fact that you see a pack of cigarettes in the candidate’s briefcase, can you make any inference whatsoever regarding how strong that habit is and how often he will have to go out for a smoke during work hours, whether his car or clothes will smell of tobacco or how likely he will be to quit or to set off a smoke alarm at the office?

4. MISTAKING STATES FOR TRAITS (and vice versa): Perhaps the most obvious example of this is nervousness. I was once interviewed at a Canadian university-college for a position as a Japanese-language instructor—my first such interview. Because the interview was entirely in Japanese, I wasn’t quite as self-assured as I would have been in English.

As a result, I finished far too many sentences with “ne”—the Japanese equivalent of the Canadian “eh” or “you know”, and sounded like a defensive Tom Cruise being grilled about Scientology: “….you know….., you know….”

If the interviewing panel inferred that being “nervous” was a permanent trait, rather than a temporary state, they would have completely misread me—a misinference they would have had no chance to correct, since I was not hired (presumably because I lived 2.5 hours away by car. But then, who knows?).

The reverse situation, in which a trait is mistaken for being merely a state, is equally easily illustrated: A candidate who has flown in for a meeting seems very sluggish and slow on his feet in the interview. The recruiter chalks it up to jet lag—a transient state, when it is in fact, in this instance, a more or less permanent trait.

5. MISTAKING REACTIVE TRAIT FOR ACTIVE TRAIT: A recruiter finds himself debating with a candidate about industry trends and concludes that the candidate is “argumentative”, “intellectually competitive”, but without determining whether the candidate was reactively argumentative or actively argumentative. That’s the difference—and a big one—between fighting back and picking a fight.

Reactive argumentativeness is likely to be a much more positive trait, to the extent that it demonstrates resistance to intimidation, confidence in one’s convictions and knowledge, assertiveness, etc., while remaining fair-minded and respectful. Active argumentativeness, on the other hand, is more likely to be an expression of sheer aggressiveness. In practice, these can be difficult to distinguish in the middle of a fast-paced interview. (Such a distinction does not apply to sandstone properties.)

However, if the candidate’s underlying or expressed attitude is “I don’t want to dominate you; but I won’t let you dominate me”, the argumentativeness is more likely to be reactive—an ingratiating attitude among members whom I’ve observed as a guest at Mensa meetings. The challenge is to ferret out that attitude.

6. MISIDENTIFICATION OF TRAIT/STATE TRIGGERS OR INHIBITORS: A job applicant is 20 minutes late for his interview. You quickly conclude he has the trait of not being a “punctual person”, having assumed that the trigger of his tardiness was his flawed character, when in fact it was a flat tire. When he explains, you also conclude that he is someone who has the trait of “making excuses”, without realizing that the one in possession of a negative trait is you, that trait being “hyper-critical” or “suspicious”.

The irony here is that you may conclude that his lateness was triggered by a tendency to be unpunctual, when in fact his tendency to be punctual was inhibited by the flat tire.

Ditto for “argumentativeness”. You may have a vested interest in recalling that the candidate “started” the verbal jousting, when in fact you did. One way this can easily happen is if you ask a “complex question”, such as “Hmmmm. You worked as an entry-level assistant for three years. Why were you content to stay so long in a job that was a bad match for you?”

That can be the trigger of a forceful exchange, as the applicant reacts to “correct” you, by pointing out that he was not content with the job, but that it was a good match in terms of providing basic experience and an industry credential, etc., etc.

7. OVER-EXTRAPOLATION TO OTHER CASES: After a number of annoying follow-up phone calls from one candidate, a recruiter may, in addition to concluding that the applicant is “rude”, “insecure”, “a pest” or “impatient”, hastily assume that the next candidate who calls more than once has the same traits—because of a momentary or acquired hyper-sensitivity to repeat phone calls (predicated on also assuming that the first candidate had any or all of those annoying traits, understood as predispositions to act in habitual ways).

8. EQUATING TRAITS AS CAUSE AND EFFECT: In the immediately preceding hypothetical situation, it might be very tempting to describe the candidates as having the trait of being “annoying”, on the basis of your having been annoyed. Describing this more abstractly, you would be inferring that a candidate had a certain trait, because of and as a cause of a response in yourself, as an effect.

However, that is as risky an inference as is concluding that Einstein had the trait of being “boring” because you were bored by his derivation of the special-relativistic time dilation from his axiom of the invariance of the velocity of light for all Galilean observers. (See? You probably got as far as “dilation” before your yawn dilated to a full-size one.)

The most relevant trait to be observed here would be your propensity to be bored by physics, not Einstein’s alleged trait of being “boring”. That is to say, your yawn would tell an observer more about you than about Einstein, or at least as much.

Such “response-identified traits”, to coin a phrase, that are clearly attributed to others on the basis of our responses, are very different from traits such as being “blue-eyed”, which exist independently of our responses to the blue-eyed person. Interestingly, many traits likely to be formally or casually identified in a candidate review, e.g., “well-organized” fall somewhere in-between on the spectrum ranging from “response-identified” and “non-response-identified” traits.

That’s because judgments about whether a candidate has traits such as “well-organized” or “shy” will depend not only on a recruiter’s individual standards of what counts as these, but also on to what extent the manifestation of the traits in an interview depended on a recruiter’s responses to the candidate during the interview. Eye color, on the other hand, and unlike the trait “perspires easily”, is never influenced by the process of being interviewed.

The One Exception

There is one exception to all of the cautionary observations made herein. It is the one instance in which the traits and states of a particular kind of rock are seen to be as complex and idiosyncratic as those of any applicant. This kind of rock may be difficult to find, although once quite plentiful. But if you ever acquire one, you will immediately make the same complex inferences about it that you should make about the average job candidate.

Interestingly, predictably and ironically, it is the one kind of rock that virtually all professional geologists regard as being outside their domain of expertise.

The “Pet Rock” of the 70s.