100 Million Reasons to Hire for Character

But because Zappos has consistently been ranked as a top place to work (even prior to this admission), I had to assume that they were pretty good at hiring – and, thus, the bad hire problem wasn’t at all unique to them. So, I set out to wrap my arms around this issue, and I’ve only just recently come to grips with it.

Does the average company or recruiter care about bad hire costs? Is it an acknowledged problem? Are they measuring it?

Today, after hundreds of conversations with business owners, recruiters, and HR executives, I think the answer to these questions is yes. Five or six years ago? Probably not.

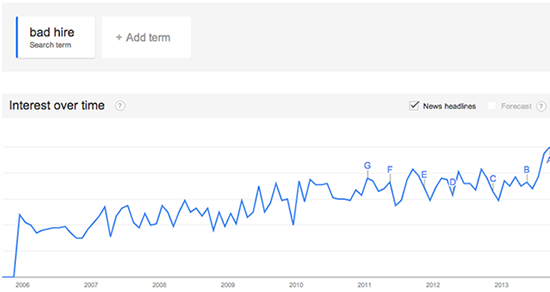

Here’s a graph from Google Trends that shows how the conversation around bad hires has increased by roughly a factor of 4 in the past 8 years (relative to overall searches).

What defines a bad hire?

CareerBuilder posted a study late last year where the company asked nearly 2,400 hiring managers to list the top characteristics of a bad hire. It wanted to know why someone turned out to be a bad hire. Those results:

- Employee didn’t produce the proper quality of work – 67 percent

- Employee didn’t work well with other employees – 60 percent

- Employee had a negative attitude – 59 percent

- Employee had immediate attendance problems – 54 percent

- Customers complained about the employee – 44 percent

- Employee didn’t meet deadlines – 44 percent

While nothing struck me as being particularly surprising on the surface, two theories emerged as I ruminated on this:

- We must be getting really good at validating candidate skills/knowledge – and training employees on new skills.

- Personal character attributes must be the ultimate determinant as to whether or not an employee turns out to be a bad hire.

The first point makes sense from the standpoint that the tools for measuring – and learning – skills have greatly evolved over the past 5-10 years. There must be an entire sector of the HR Technology industry devoted toward building better ways to verify candidate skills in inventive, predictive, and efficient ways. The data above backs this up as, at best, hard skills might impact two of the six bad hire qualities cited.

The second point makes sense simply due to the fact that each of the qualities cited in the study are reflections of personal character traits (or, more accurately, flaws). Not to be confused with personality traits (which a person can’t really control), character attributes are driven by a personal belief system. They are controllable. They are changeable. For example, I can decide whether or not I want to be a cooperative team member, and whether or not I’m going to go above and beyond or simply do the bare minimum. These decisions – ones that we make as employees each and every day – are the drivers of the bad hire problem.

How can we better screen for the character attributes that impact bad hiring rates?

Of course, character isn’t a black-and-white issue. We’re dealing in the uncertain realm of the grayscale.

The good news is that there is an age-old solution out there that we’re all familiar with. That’s right, I’m referring to reference checks. Now (WAIT!) before you tell me how worthless reference checks are, let’s quickly revisit the intent.

Before LinkedIn, before email, even before electronic resumes, we had reference checks. Why? My guess is that reference checks were once (1) far more valuable and (2) far more efficient than they are today. Companies have always wanted to make the best hiring decisions, so it makes sense that the reference check was once a viable method for collecting important candidate data. I’d also go so far as to suggest that character was understood to be of greater importance 20 years ago than it is today. So, it wouldn’t surprise me if a reference check in 1993 was a conversation hitting on the very bad hire qualities listed in the CareerBuilder study from 2012. Admittedly, though, these personal theories would be tough to prove.

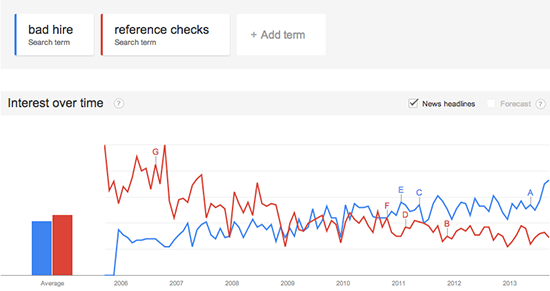

Moving on, and fast-forwarding to today, it’s clear that the reference check has devolved over time thanks to legal concerns, information inflation, and a particular obsession with skills that comes with a buyer’s market, among other things. Interestingly, just as we were losing interest in reference checks we were becoming more interested in the bad hire discussion.

Here’s another Google Trends graph illustrating this point.

How do we overcome time and data constraints?

In the same CareerBuilder study referenced above, hiring managers were asked what they thought contributed to a bad hiring decision. Here are the most common responses:

- Needed to fill the job quickly – 43 percent

- Insufficient talent intelligence – 22 percent

- Sourcing techniques need to be adjusted per open position – 13 percent

- Fewer recruiters due to the recession has made it difficult to go through applications – 10 percent

- Didn’t check references – 9 percent

- Lack of strong employment brand – 8 percent

- One-in-four employers (26 percent) stated they weren’t sure why they made a bad hire and said sometimes you just make a mistake.

Essentially, these are all different ways of saying the same two things – as there are consistent underlying constants at play here:

- Time – Suggesting that there wasn’t enough time to seek more candidate data

- Data – Suggesting that more candidate data wasn’t available

To get over both of these hurdles and effectively reduce bad hire costs, we’re going to have to start thinking differently.To do so, I propose we do two simple things.

First, continue to embrace the bad hire discussion. Technology has afforded us improvements in the overall efficiency of recruiting and hiring but, as Tony Hsieh reminded us, we still have a long way to go. Not to mention that the dynamics of a virtual workplace and the global economy seem to be presenting new pressures and challenges in finding – and retaining – the right talent (another conversation for another day).

Second, but equally important, we need to re-embrace the concept of character-based reference checks. This stuff matters. Sure, there are more efficient ways to do this than others (I’m definitely a bit biased here), but the important thing is to make room for reference checking in some fashion in your screening process. Unfortunately, character traits cannot be as accurately self-reported as personality traits – so we must go the proverbial extra mile. Not doing so is gambling, taking an unnecessary risk, plain and simple. After all, the data exists. We all exhibit character. Perhaps it’s time to get a bit creative.